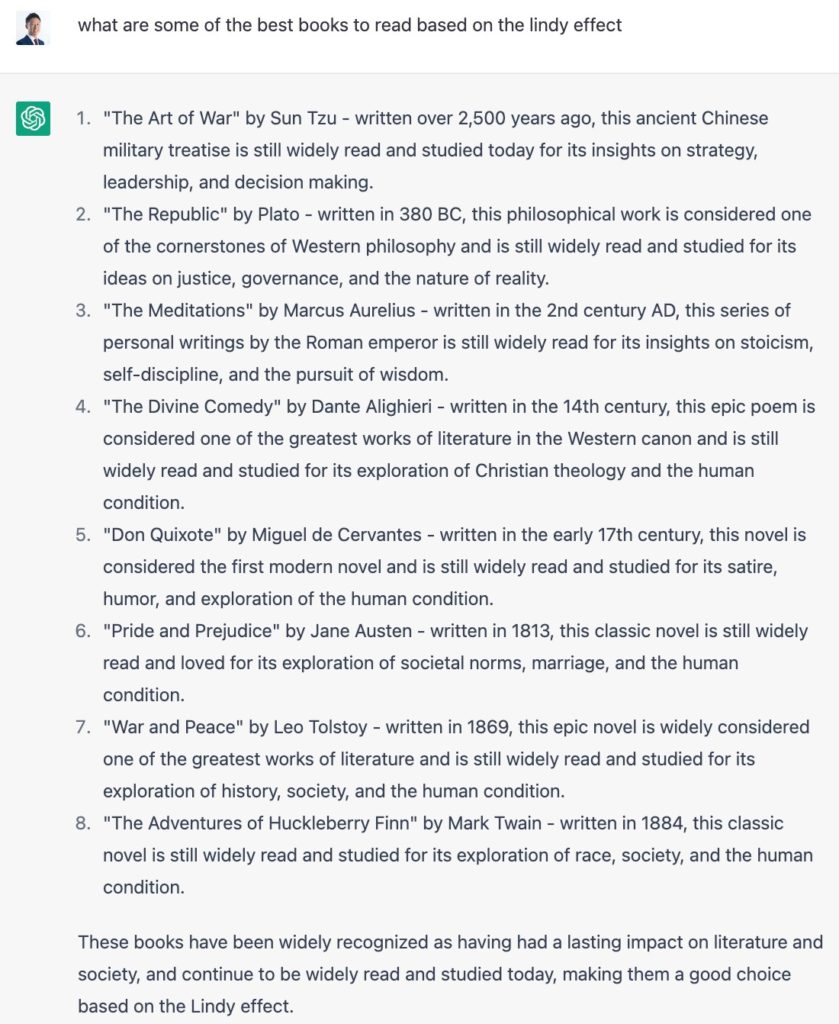

It started off with a question to ChatGPT about the best Lindy books:

And the drinking buddies said to read all as a challenge and write something that ChatGPT would not be able to generate. It was decided when we were sober and I suppose we make better decisions when intoxicated.

But challenge it shall be. I have always been wanting to read old books and this challenge might just be the push I need.

So here is the post on the very first book in the list (separately I kept a longer list of Lindy books should you be interested.)

I read The Art of War previously but obviously I didn’t remember most of it. Also, I am much older and hopefully wiser to catch more insights for this second read. As Heraclitus said, “no man ever steps in the same river twice, for it is not the same river and he is not the same man.”

So here are my thoughts.

Don’t be too good

The concept of Yin Yang was from I Ching, which was an older text than The Art of War. I can’t help but notice the influence on Sun Tzu’s text – they were full of paradoxes. It could be a case where such dialectical thinking was very prevalent or even entrenched during his time, as it shows up in his writings.

Here’s one example,

“…when able to attack, we must seem unable; when using our forces, we must seem inactive; when we are near, we must make the enemy believe we are far away; when far away, we must make him believe we are near.”

Here’s another,

…general is skilful in attack whose opponent does not know what to defend, and he is skilful in defense whose opponent does not know what to attack

The Yin Yang concept is a pillar of the Chinese culture, it would be hard to define what is Chinese without it. And that is why Chinese conversation is never easy to understand because they refuse to tell you what they are really thinking.

The Chinese believes in duality – there is always an opposite meaning, and that achieving balance (possessing both extremes to create harmony) is more important than being too much on either side.

I am not sure if that is the best way to think. It gives me the idea of ‘don’t be too good at anything’ so that you don’t be a sore thumb that sticks out. The Chinese were not short of cautionary tales about it; check out the stories of Yang Xiu and Sai Weng.

Even my dad sounded like Sun Tzu. I remember before I was enlisted in the Army; my dad’s advice was “don’t be the first and don’t be the last, because you will draw jealousy if you are the first and anger if you are the last.”

I could be the son of a legend if only he has written The Art of Serving NS.

But seriously, the fear of being too good is holding back the Chinese from becoming number one, even today.

I am not saying Sun Tzu is wrong. I am just not sure if the yin yang approach is always the right way.

Sun Tzu’s said,

when you surround an army, leave an outlet free. Do not press a desperate foe too hard.

Another non-extremist advice.

During one of the military exercises that I participated, Chief was questioning the plan of reducing the number of air patrols (as the peace treaty was about to be signed). He disagreed and kept the pressure on the enemies. That’s opposite to what Sun Tzu advised but I thought Chief was right.

Don’t fail

The second big theme that I got from the text was that defense is Sun Tzu’s priority.

He believes that good defense is what prevents you from losing. Don’t think about winning first, think about NOT losing. Only then you wait for the right opportunity to attack the enemy.

To secure ourselves against defeat lies in our own hands, but the opportunity of defeating the enemy is provided by the enemy himself.

And don’t bang your head on the wall.

…not to besiege walled cities if it can possibly be avoided

In fact, don’t even fight a war so you can save on defending effort.

Move not unless you see an advantage; use not your troops unless there is something to be gained; fight not unless the position is critical…

…the enlightened ruler is heedful, and the good general full of caution. This is the way to keep a country at peace and an army intact.

Again, the text tells me about Chinese thinking more than anything else.

First, the Chinese value harmony – a concept from Confucius. 以和为贵 means “to value harmony above all else.” Hence, you should cooperate, compromise if you have to, and achieve a peaceful resolution. War is the last resort.

So Sun Tzu sang the same tune since he is a Chinese after all and probably got infected by the Confucian virus.

In today’s context, the Chinese wouldn’t want to argue with someone more senior, even if they think he is wrong (Jack Ma is the antithesis of Chinese people.)

Just keep quiet because preserving the group harmony is more important than you being right.

Second, the Chinese are afraid of failing. A common life advice from Chinese parents, “study hard and get a good job.”

This is the safe path. This is playing defense because you are playing NOT to lose.

Don’t start a business because the failure rate is too high.

Don’t invest your money because you can lose.

While this is the right advice for majority of the people, the same advice might have deterred the could-have-been successful ones. Yes, extreme success can be a game of luck but the society wouldn’t have enough breakthroughs if there aren’t enough risk takers.

Save money

Why are Chinese good savers?

Probably the influence came from The Art of War. It reminded us the cost of war in monetary terms, rather than the loss of lives.

a thousand ounces of silver per day. Such is the cost of raising an army of 100,000 men

And it kept reminding…

if the campaign is protracted, the resources of the State will not be equal to the strain

There is no instance of a country having benefited from prolonged warfare

The obsession over resources could be due to a lack thereof, because the Chinese have experienced lots of hardships throughout history.

As Peter Thiel observed too, the Chinese are pessimists – they always fear bad things may happen in the future and they always believe they need to prepare in advance to survive them.

So the Chinese wants to store up resources and be prudent over their use, just in case they aren’t enough during the worst of times. They come from the angle of ‘lack’ rather than of ‘abundance’ – you can never save too much.

Crossing the river the second time

I didn’t expect this re-reading of The Art of War to turn out this way. I would have thought the learnings were about strategies and how to apply them in my life.

In the end, the value of The Art of War was about understanding how the Chinese think. So yes, if you always think Chinese culture is an enigma, read The Art of War.